What impulse spending can say about you

It's never about the thing you bought

I once worked at a fancy Cuban restaurant with a busboy named Jason, who came back from his break one day and announced that he had just bought a $3,000 art print.

Like me, Jason was in his 20s and living at home. I was squirreling away cash for my move to Brooklyn, but Jason didn’t seem to have a plan.

Every night, we waited on people with way more money than us: students at Yale who could afford $150 dinners, adults who had remunerative careers (unlike working at a restaurant and saying you’re a writer). Often, they’d drop the credit card on the table when I approached with the bill, not even deigning to look at the price. I longed for that kind of laissez-faire attitude with my money.

And what scared me more than spilling a mojito on a rich person or getting yelled at by the kitchen staff was thinking that I might not ever get close to being like those people dropping their Amex’s at the end of a meal, looking completely relaxed and comfortable.

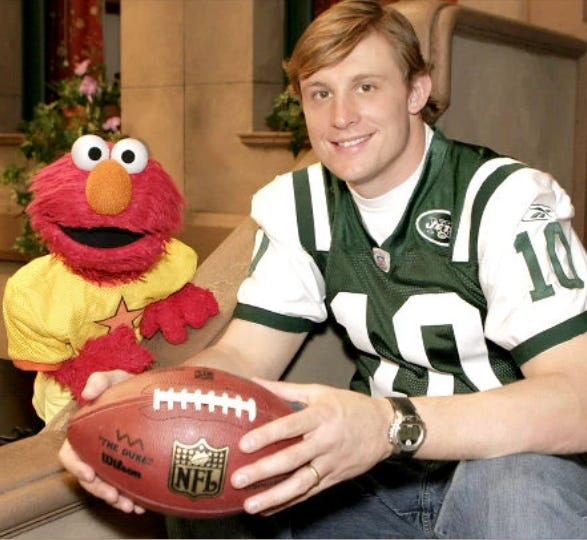

I was scared I might end up like Robert, an older bullying waiter who started working in restaurants as a young actor. Robert greeted me every afternoon from his hangover in a darkened corner of the restaurant, shouting “Chad!” (I had a passing resemblance to NFL quarterback Chad Pennington)

Jason’s big art purchase never made sense to me until years later, when I was dealing with a health crisis and feeling hopelessly distant from the life I wanted.

I’d always focused on the randomness of Jason spending $3000 on a piece of art, but never tried to empathize with what he may have been looking for when he spent that money.

Maybe he was thinking of the people we served in the restaurant, and when he walked by the art gallery that day he thought, why not me? When is it going to be my turn?

Maybe when the salesperson put the bill on the counter, Jason just dropped his credit card without even looking at it. He felt he needed this purchase, not because he needed art. (They sold art posters at the museum down the street.) Maybe he needed the certainty that this phase we were in—folding napkins in a basement restaurant—was just a phase.

Buying stuff is easy. Understanding why we do it is not.

Think about the loner who never invites anyone to his house but builds a bar for entertaining. Or, the person who freaks out about the price of eggs, but spends $600/month on their new car lease.

Some personal-finance experts make a living ripping people to shreds for decisions like this. They act as if spending money is simply an exercise in rationality. It’s not.

We spend to express who we are and who we want to be.

And sometimes, if people don’t believe they can get where they want to be by staying on course (planning, saving, etc.), they try to leapfrog the process and spend money in a way that seems crazy or irresponsible from the outside.

Maybe Jason wasn’t just spending money for the thrill of it. Maybe he was impatient with the distance between his current life and the one he imagined. I can relate.

Money isn’t just a tool; its a language. When we spend, we’re not just buying things. We’re making quiet (and sometimes not so quiet) declarations of what we value or who we hope to become.

The trouble comes when we try to shortcut the becoming part.

We want to feel like the person who’s already made it, not the one still bussing tables and waiting for life to happen.

So, sometimes we spend in ways that seem reckless and unthinking because we’re tired of waiting to feel better about our money. And when we do, it doesn’t help to shame ourselves for it. Money mistakes aren’t moral failures. We all make them, and usually they’re just moments of impatience.

The real work isn’t punishing ourselves into better habits as some finance experts (ahem) would have you believe.

The real work is learning to practice patience instead of panic, compassion instead of criticism.

Have you ever spent way too much on something you regretted later? What did you learn from the experience? I’d love to hear about it.

Until next time,

Chad Dan